Main results

Week 3: Supervised Text Classification

Dr. Philipp K. Masur

are to be believed, the invention of artificial intelligence inevitably leads to apocalyptic wars between machines and their makers

It begins with today’s reality: computers learning how to play simple games and automate routines

They later are given control over traffic lights and communications, followed by military drones and missiles

This evolution takes a bad turn once computers become sentient and learn how to teach themselves….

Having no more need for human programmers, humankind is simply deleted…

Is this what machine learning is about?

(Stills from the movies “Ex Machina” and “Her”)

Machine learning is the study of computer algorithms that can improve automatically through experience and by the use of data

The field originated in an environment where the available data, statistical methods, and computing power rapidly and simultaneously evolved

Due to the “black box” nature of the algorithm’s operations, it is often seen as a form of artificial intelligence

But in simple term: Machines are not good at asking questions or even knowing what questions are

They are much better in answering them, provided the question is stated in a way that a computer can comprehend (remember the main challenge of text analysis?)

Machine learning is most successful when it augments, rather than replaces, the specialized knowledge of a subject-matter expert.

Machine learning is most successful when it augments, rather than replaces, the specialized knowledge of a subject-matter expert.

Machine learning is used in a wide variety of applications and contexts, such as in businesses, hospitals, scientific laboratories, or governmental organizations

In communication science, we can use these techniques to automate text analysis!

Lantz, 2013

Applying machine learning in practical context:

Applying machine learning in practical context:

1. What is machine learning?

2. Supervised text classification

3. Examples from the literature

4. Outlook and conclusion

Differences between supervised and unsupervised approaches.

In the previous lecture, we talked about deductive approaches (e.g., dictionary approaches)

These are deterministic and are based on text theory (e.g., happy -> positive, hate -> negative)

Yet, natural language is often ambiguous and probabilistic coding may be better

Dictionary-based or generally rule-based approaches are not very similar to manual coding; a human being assesses much more than just a list of words!

Inductive approaches promise to combine the scalability of automatic coding with the validity of manual coding (supervised learning) or can even identify things or relations that we as human beings cannot identify (unsupervised learning)

Algorithms build a model based on sample data, known as “training data”, in order to make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed to do so

Combines the scalability of automatic coding with the validity of manual coding (requires pre-labeled data to train algorithm)

Examples:

Algorithm detects clusters, patterns, or associations in data that has not been labeled previously, but researcher needs to interpret results

Very helpful to make sense of new data (similar to cluster analysis or exploratory factor analysis)

Examples:

Training algorithms to make good predictions!

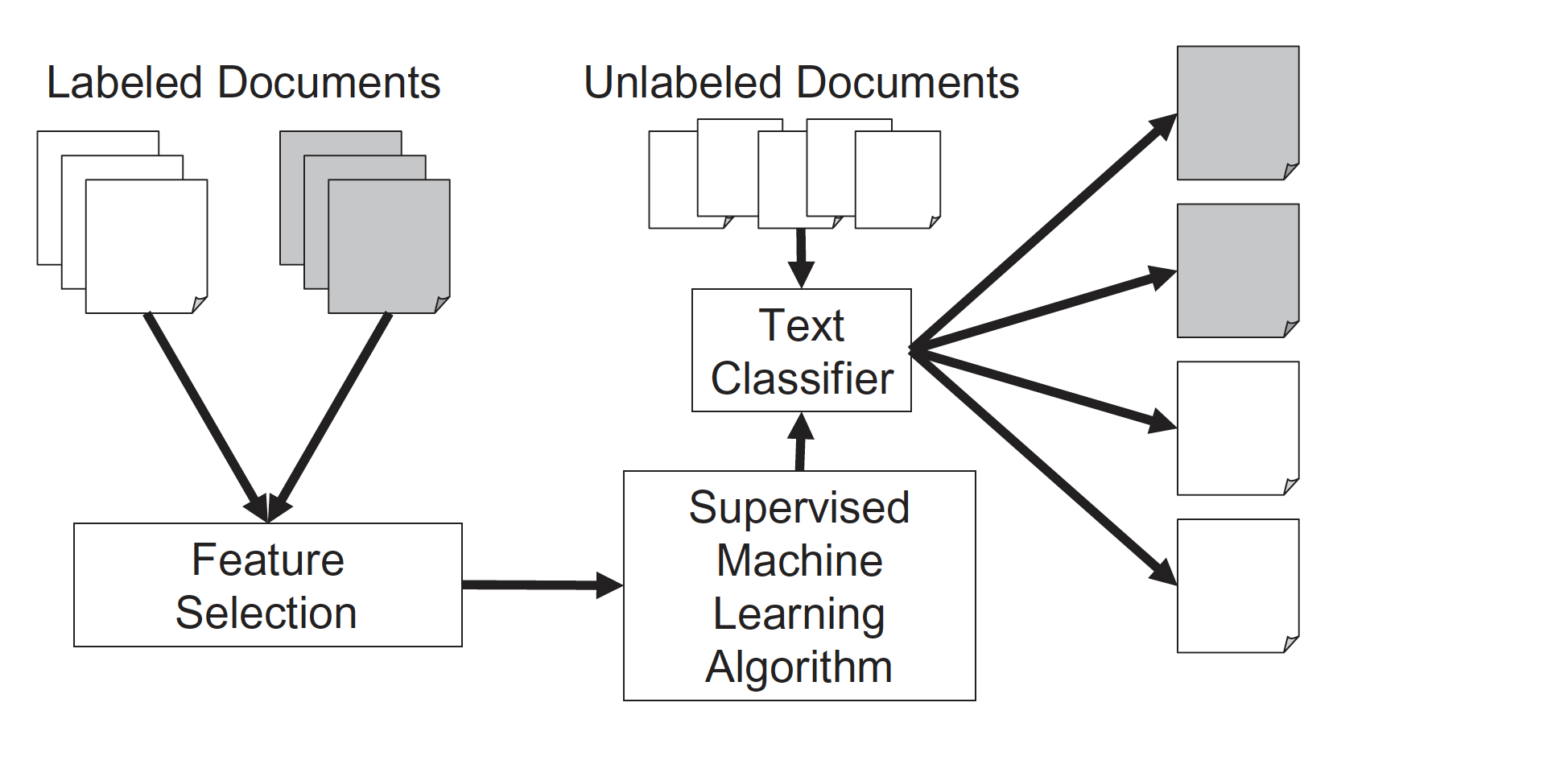

We can now use machine learning models to classify text into specific sets of categories. This is known as supervised learning. The basic process is:

1. Manually code a small set of documents (say N = 1,000) for whatever variable(s) you care about

2. Train a machine learning model on the hand-coded data, using the variable as the outcome of interest and the text features of the documents as the predictors

3. Evaluate the effectiveness of the machine learning model via cross-validation (test it on new data/gold standard)

4. Once you have trained a model with sufficient predictive accuracy, apply the model to the remaining set of documents that have never been hand-coded (e.g., N = 100,000) or use it in the planned application (e.g., a spam filter detection software)

Suppose we would want to develop a tool to automatically filter spam messages

How would you do this if you could only use a dictionary?

Machine learning solution

The resulting “classifier” can then be integrated in a software tool that can be used to detect spam mails automatically

Machine learning is thus similar to normal statistical modeling

Learn \(f\) so you can predict \(y\) from \(x\):

y based on x.

Goal of ‘normal’ modeling: explaining/understanding

Goal of machine learning: best possible prediction

Note: Machine learning models often have 1000’s of collinear independent variables and can have many latent variables!

independent of language and topic; we only need consistently coded training material

can be connected to traditional content analysis (same operationalization, similar criteria in terms of validity and reliability)

efficient (analysis of very large samples and text corpora possible)

Requires large amounts of (manually) coded training data

Requires in-depth validation

How do these algorithms work?

There are many different “algorithms” or classifiers that we can use:

Most of these algorithms have certain hyperparameters that need to be set

Unfortunately, there is no good theoretical basis for selecting an algorithm

Computes the prior probability ( P ) for every category ( c = outcome variable ) based on the training data set

Computes the prior probability ( P ) for every category ( c = outcome variable ) based on the training data set

Computes the probability of every feature ( x ) to be a characteristic of the class ( c ); i.e., the relative frequency of the feature in category

For every probability of a category in light of certain features ( P(c|X) ), all feature probabilities ( x ) are multiplied

The algorithm hence chooses the class that has highest weighted sum of inputs

Lantz, 2013

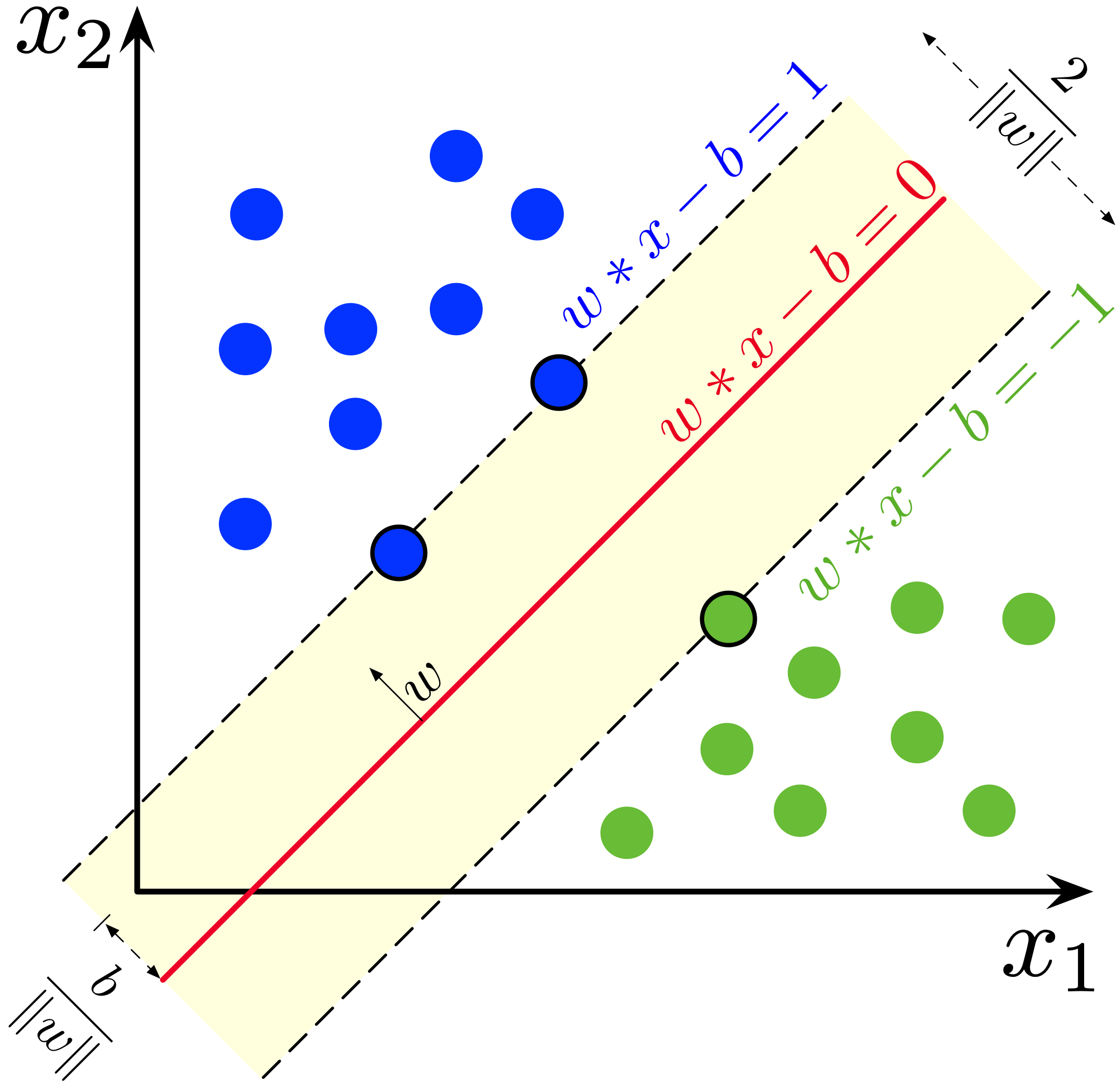

Very often used machine learning method

Very often used machine learning method

Can be imagined as a “surface” that creates a boundary between points of data plotted in a multidimensional space representing examples and their feature values

Tries to find decision boundary between points that maximizes margin between classes while minimizing errors

More formally, a support-vector machine constructs a hyperplane or set of hyperplanes in a high- or infinite-dimensional space

Lantz, 2013

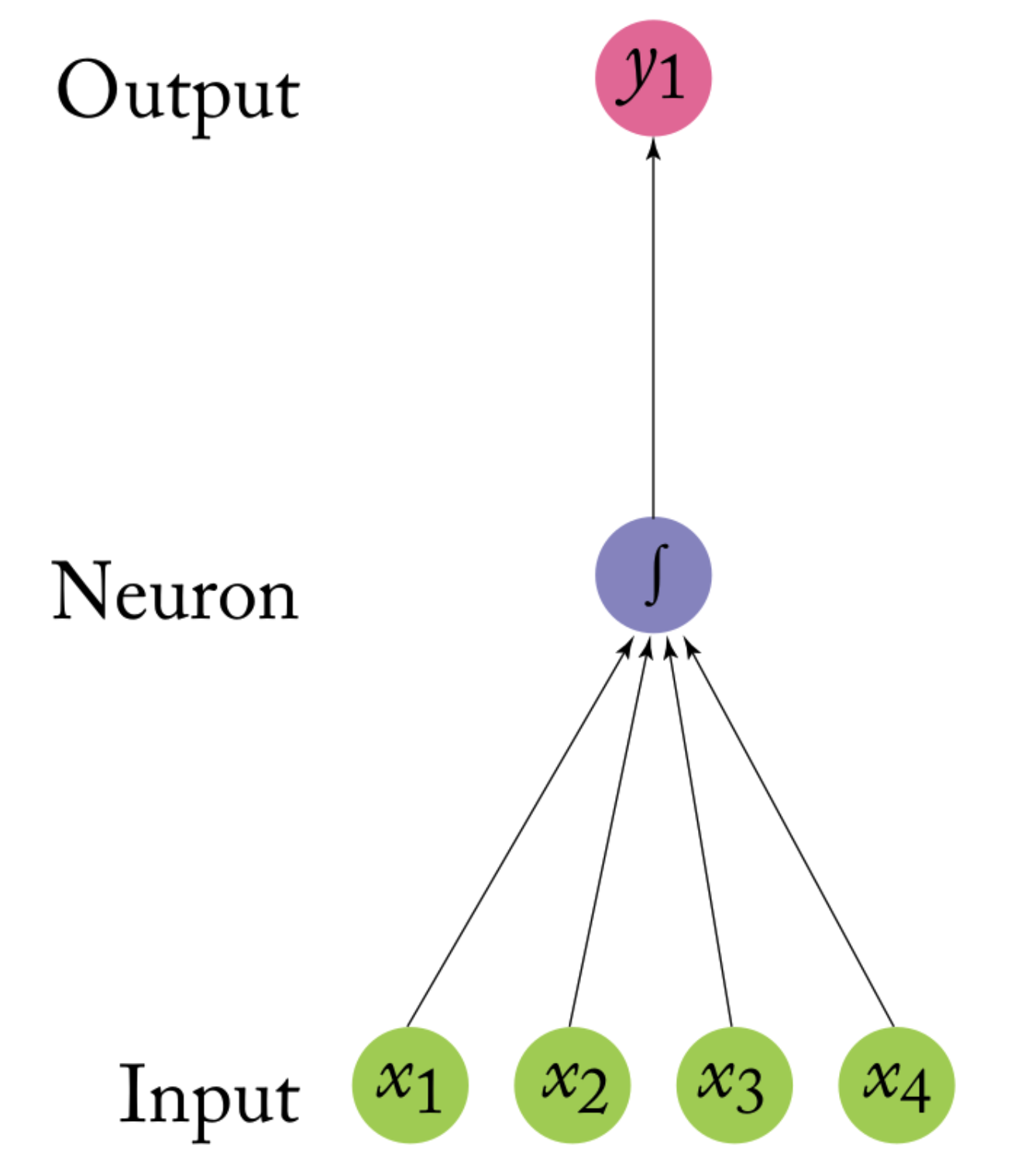

Inspired by human brain (but abstracted to mathematical model)

Inspired by human brain (but abstracted to mathematical model)

Each ‘neuron’ is a linear model with activation function:

\(y = f(w_1x_1 + … + w_nx_n)\)

Normal activation functions: logistic, linear, block, tanh, …

Each neuron is practically a generalized linear model

Networks differ with regard to three main characteristics:

Universal approximator: Neural Networks with single hidden layer can represent every continuous function

Lantz, 2013

Sufficiently complex algorithms can “predict” all training data perfectly

But such an algorithm does not generalize to new data

Essentially, we want the model to have a good fit to the data, but we also want it to optimize on things that are specific to the training data set

Problem of under- vs- overfit

Regularization

Out-of-sample validation detects overfitting

In sum, we need to validate our new classifier on unseen data

Best practices and processes.

Models (almost) always overfit: performance on training data is not a good indicator of real quality

Solution

So… why don’t we do this with statistics?

This data is scraped from the “Vagalume” website, so it depends on their storing and sharing millions of song lyrics (not really representative or complete)

Many different songs, but not all types of music are represented in this data set

# A tibble: 161,289 × 10

# Groups: SLink [161,289]

ALink SName SLink Lyric Idiom Artist Songs Popularity Genre Genres

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 /10000-maniacs/ More … /100… "I c… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

2 /10000-maniacs/ Becau… /100… "Tak… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

3 /10000-maniacs/ These… /100… "The… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

4 /10000-maniacs/ A Cam… /100… "A l… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

5 /10000-maniacs/ Every… /100… "Tru… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

6 /10000-maniacs/ Don't… /100… "Don… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

7 /10000-maniacs/ Acros… /100… "Wel… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

8 /10000-maniacs/ Plann… /100… "[ m… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

9 /10000-maniacs/ Rainy… /100… "On … ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

10 /10000-maniacs/ Anthe… /100… "For… ENGL… 10000… 110 0.3 Rock Rock;…

# … with 161,279 more rowsContains artist name, song name, lyrics, and genre of the artist (not the song)

The following genres are in the data set:

d %>%

ungroup %>%

filter(Artist == "Britney Spears" & SName == "...Baby One More Time") %>%

select(Artist, SName, Lyric, Genre)# A tibble: 1 × 4

Artist SName Lyric Genre

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 Britney Spears ...Baby One More Time Oh baby baby. Oh baby baby (wow). Oh baby baby. How was I supposed to know?. That something wa… Pop d %>%

ungroup %>%

filter(Artist == "Drake" & SName == "God's Plan") %>%

select(Artist, SName, Lyric, Genre)# A tibble: 1 × 4

Artist SName Lyric Genre

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 Drake God's Plan "Yeah they wishin' and wishin' and wishin' and wishin'. They wishin' on me, yuh. I been movin' calm, don't start … Hip …Many machine learning algorithms are non-deterministic

Random initial state and/or random parameter improvements - Even deterministic algorithm require random data split

Problem: research is not replicable, outcome may be affected

For replicability: set random seed in R: set.seed(123)

For valid outcome: repeat X times and report average performance

Corpus consisting of 116,190 documents and 8 docvars.

/10000-maniacs/more-than-this.html :

"I could feel at the time. There was no way of knowing. Falle..."

/10000-maniacs/because-the-night.html :

"Take me now, baby, here as I am. Hold me close, and try and ..."

/10000-maniacs/these-are-days.html :

"These are. These are days you'll remember. Never before and ..."

/10000-maniacs/a-campfire-song.html :

"A lie to say, "O my mountain has coal veins and beds to dig...."

/10000-maniacs/everyday-is-like-sunday.html :

"Trudging slowly over wet sand. Back to the bench where your ..."

/10000-maniacs/dont-talk.html :

"Don't talk, I will listen. Don't talk, you keep your distanc..."

[ reached max_ndoc ... 116,184 more documents ]# Set seed to insure replicability

set.seed(42)

# Sample rows for testset and create subsets

testset <- sample(docnames(music), nrow(d)/2)

music_test <- music %>%

corpus_subset(docnames(music) %in% testset)

music_train <- music %>%

corpus_subset(!docnames(music) %in% testset)

# Define outcome variable for each set

genre_train <- as.factor(docvars(music_train, "Genre"))

genre_test <- as.factor(docvars(music_test, "Genre"))The procedure is always the same

Split data into train and test set

We store the outcome variable (Genre) for each subset

Step 1: Tokenization (including removing ‘noise’) and normalization

Step 2: Removing stop words

Step 3: Stemming

Step 4: Create document-feature matrix (DFM)

Step 5: Remove too short (< 2 characters) and rare words

(Step 6: Transforms the dtm so that words with a high document frequency weight less)

Call:

textmodel_nb.dfm(x = dfm_train, y = genre_train)

Class Priors:

(showing first 3 elements)

Hip Hop Pop Rock

0.3333 0.3333 0.3333

Estimated Feature Scores:

take now babi hold close tri understand desir hunger fire breath

Hip Hop 0.001212 0.001709 0.001888 0.0006368 0.0003482 0.0008651 0.0003373 4.339e-05 2.898e-05 0.0003382 0.0002871

Pop 0.001912 0.002209 0.003575 0.0012459 0.0007566 0.0013738 0.0005118 1.710e-04 6.059e-05 0.0007605 0.0006797

Rock 0.002145 0.002460 0.002282 0.0013524 0.0007455 0.0015209 0.0006004 2.822e-04 1.040e-04 0.0010468 0.0008306

love banquet feed come way feel command hand sun descend hurt

Hip Hop 0.001688 1.010e-05 1.329e-04 0.001310 0.001060 0.001011 3.257e-05 0.0007522 0.0001953 8.027e-06 0.0003476

Pop 0.004675 7.163e-06 9.344e-05 0.002088 0.001887 0.002379 3.420e-05 0.0011299 0.0007235 2.252e-05 0.0007979

Rock 0.003456 1.822e-05 2.855e-04 0.002653 0.002062 0.002207 8.816e-05 0.0012946 0.0011366 5.312e-05 0.0007014

night belong lover us caus doubt alon ring

Hip Hop 0.0007309 0.0000717 0.0001143 0.0009473 0.001716 0.0001802 0.0003117 0.0003029

Pop 0.0016766 0.0002989 0.0005302 0.0012290 0.002201 0.0002322 0.0008661 0.0003434

Rock 0.0018035 0.0004535 0.0005678 0.0014138 0.001477 0.0002986 0.0012920 0.0004085To see how well the model does, we test it on the test (held-out) data

For this, it is important that the test data uses the same features (vocabulary) as the training data

The model contains parameters for these features, not for words that only occur in the test data

In other words, we have to “match” or “align” the train and test data

# Matching

dfm_test <- music_test %>%

tokens(remove_punct = T,

remove_numbers = T,

remove_symbols = T) %>%

tokens_remove(stopwords('en')) %>%

tokens_wordstem %>%

dfm %>%

dfm_match(featnames(dfm_train)) %>%

dfm_tfidf()

# Actual prediction

nb_pred <- predict(m_nb, newdata = dfm_test)

head(nb_pred, 2)/10000-maniacs/more-than-this.html /10000-maniacs/these-are-days.html

Rock Rock

Levels: Hip Hop Pop RockAs we can see in the confusion matrix, there are a lot of false positives and false negatives!

Overall Accuracy: 64.71%

Precision, Recall and F1-Score are not too good for each genre

Reference

Prediction Hip Hop Pop Rock

Hip Hop 7106 2501 3315

Pop 1012 7073 2849

Rock 1166 9659 23414When we refit the model with support vector machines, there are still a lot of false positives and false negatives

Overall Accuracy: 69.66%

However, Precision, Recall and F1-Score all have improved!

Reference

Prediction Hip Hop Pop Rock

Hip Hop 6509 1228 796

Pop 1682 10297 5117

Rock 1093 7708 23665bind_rows(cm_nb2, cm_svm2) %>%

bind_cols(Model = c(rep("Naive Bayes", 3),

rep("SVM", 3))) %>%

pivot_longer(Precision:F1) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = Genre,

y = value,

fill = Model)) +

geom_bar(stat= "identity",

position = "dodge",

color = "white") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Pastel1") +

facet_wrap(~name) +

coord_flip() +

ylim(0, 1) +

theme_grey() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

Task difficulty

Amount of training data

Choice of features (n-grams, lemmata, etc)

Text preprocessing (e.g., exclude or include stopwords?)

Tuning of algorithm (if required)

Scharkow, 2013

How is this used in research?

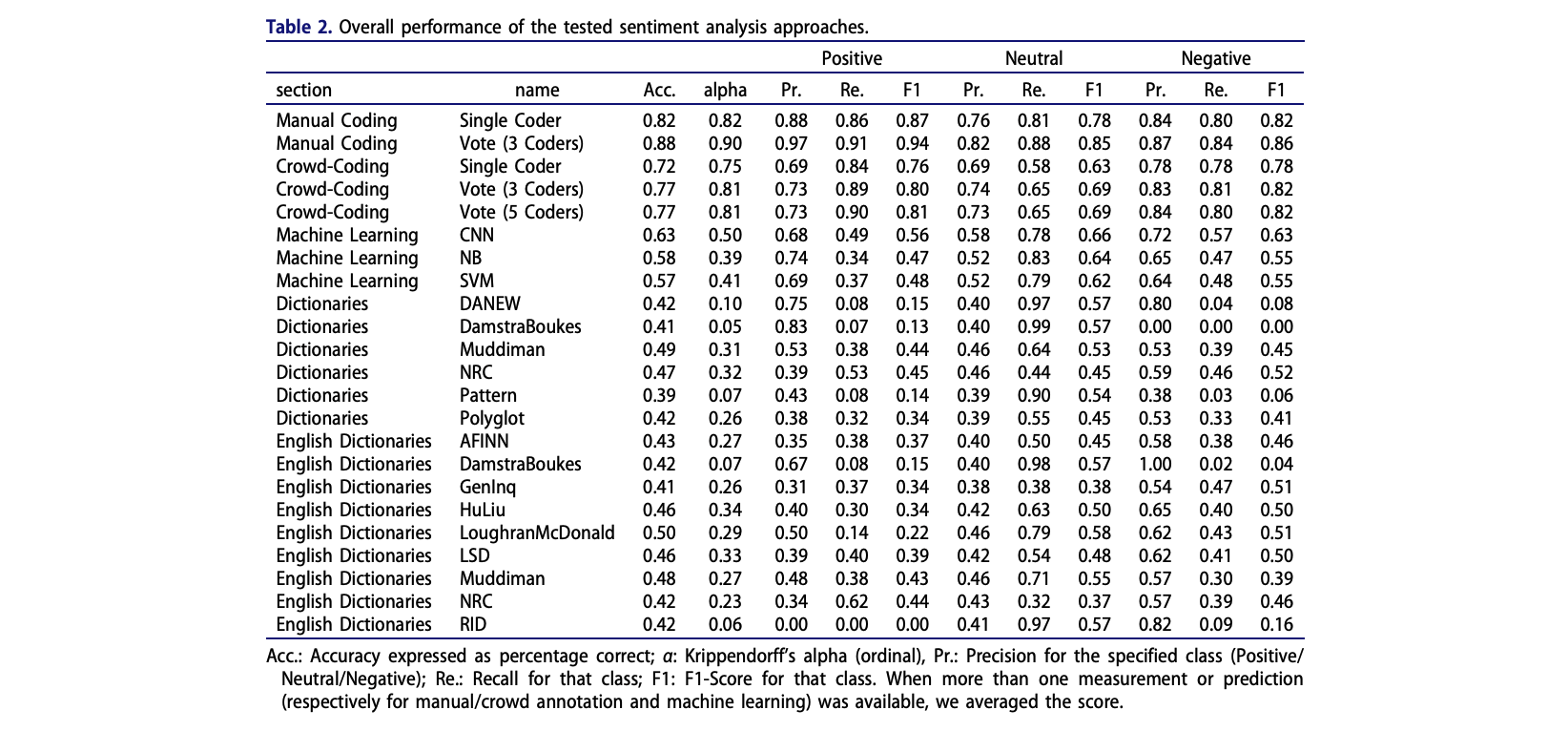

Van Atteveldt et al. (2021) re-analysised data reported in Boukes et al. (2020) to understanding the validity of different text classification approaches

The data incldued news from a total of ten newspapers and five websites published between February 1 and July 7, 2015:

They analyzed the paper using different methods and compared the results

Investigated performance results of all models

Manual coding still outperforms all other approaches

Supervised text classification (particularly deep learning) is better than dictionary approaches (not too surprising)

Particularly supervised learning gets better with more training data (more is more!)

Nonetheless strongly depends on quality of training data

Recommendation for dictionary: Apply any applicable off-the-shelf dictionaries and if any of these is sufficiently valid as determined by comparison with the gold standard, use this for the text analysis

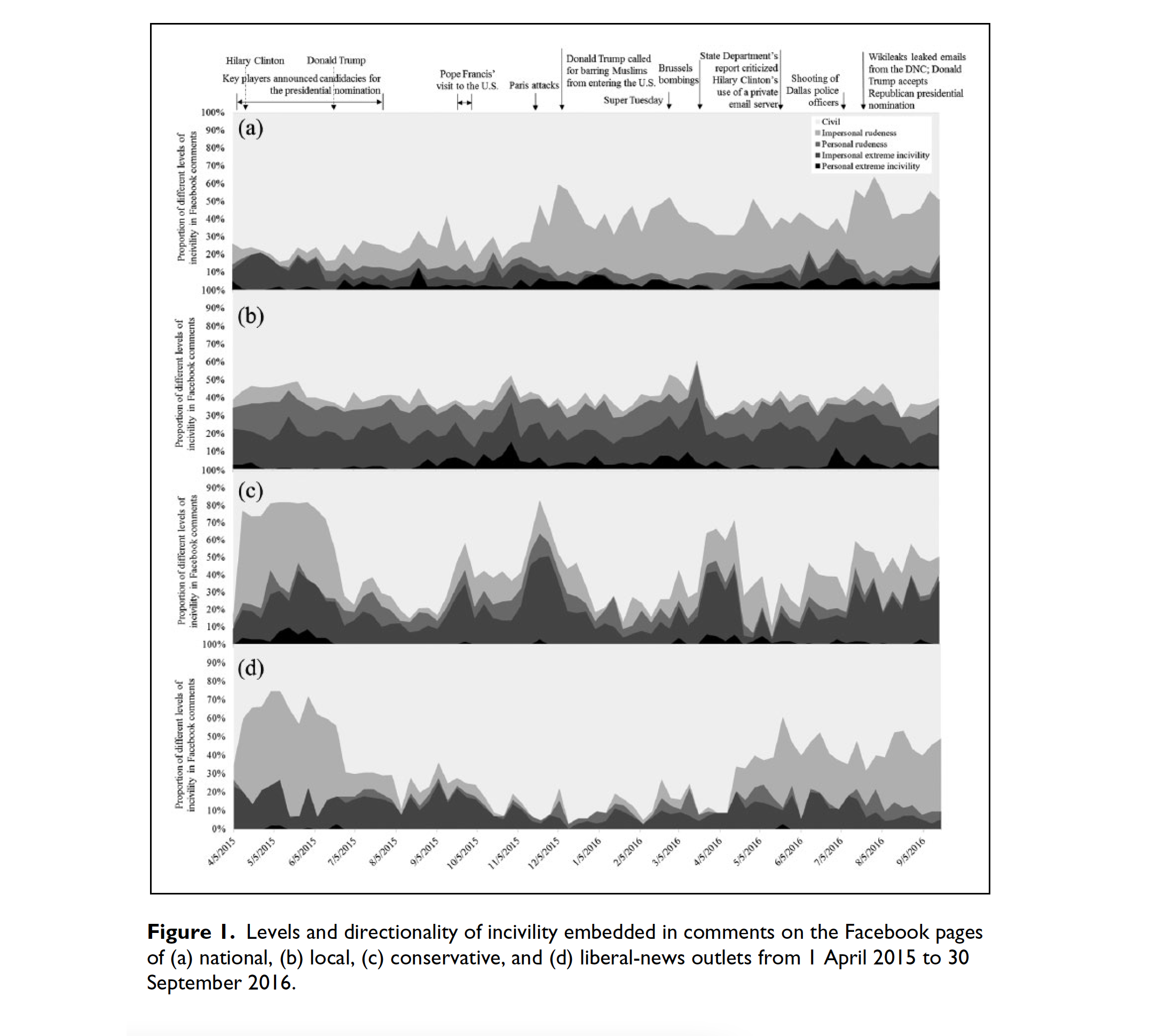

Study examined the extent and patterns of incivility in the comment sections of 42 US news outlets’ Facebook pages in 2015–2016

News source outlets included

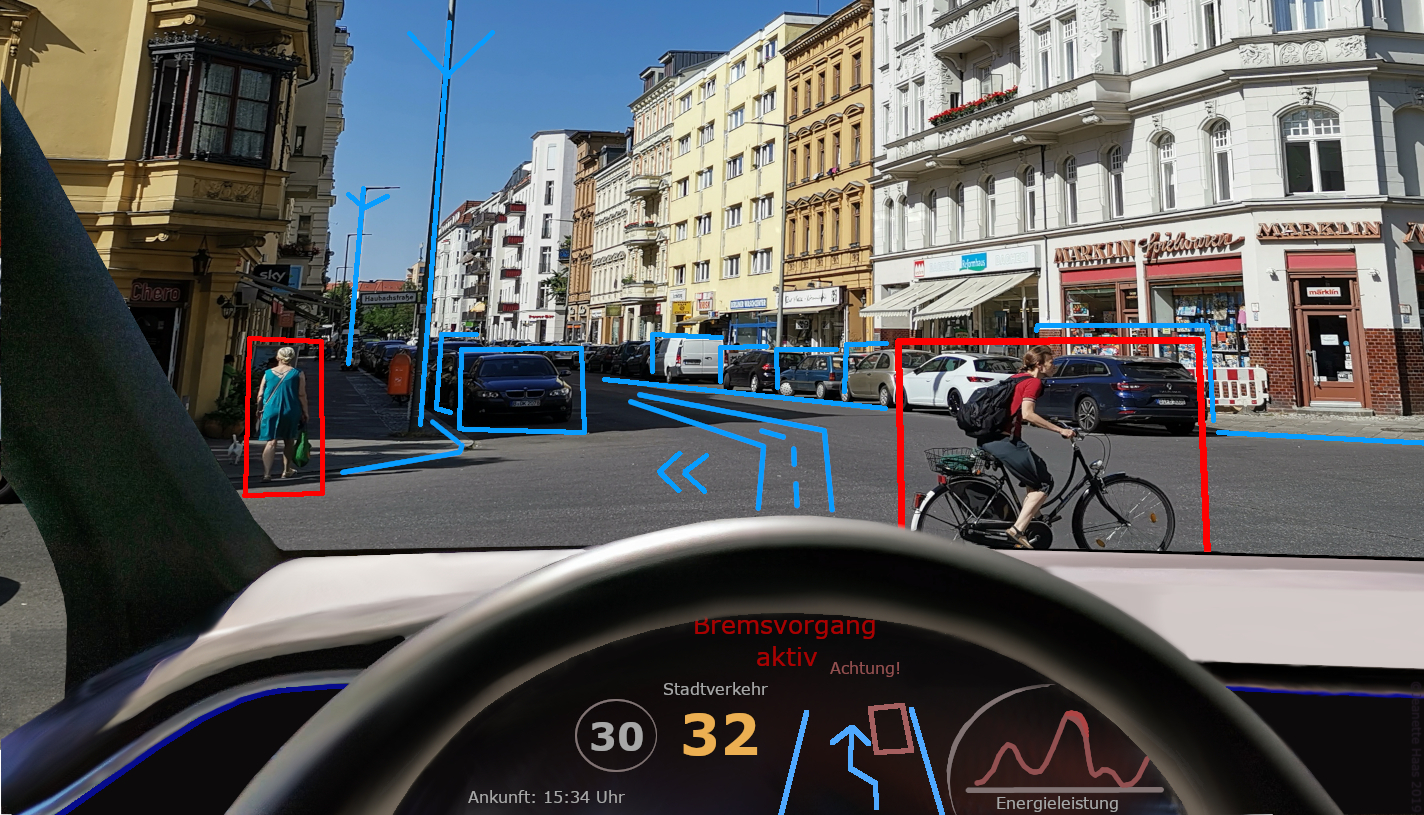

Implemented a combination of manual coding and supervised machine learning to code comments with regard to:

Despite several discernible spikes, the percentage of extremely uncivil personal comments on national-news outlets’ pages shifted only modestly

On conservative outlets’ Facebook pages, the proportions of both extremely uncivil and rude comments fluctuated dramatically across the sampling window

Su et al., 2018

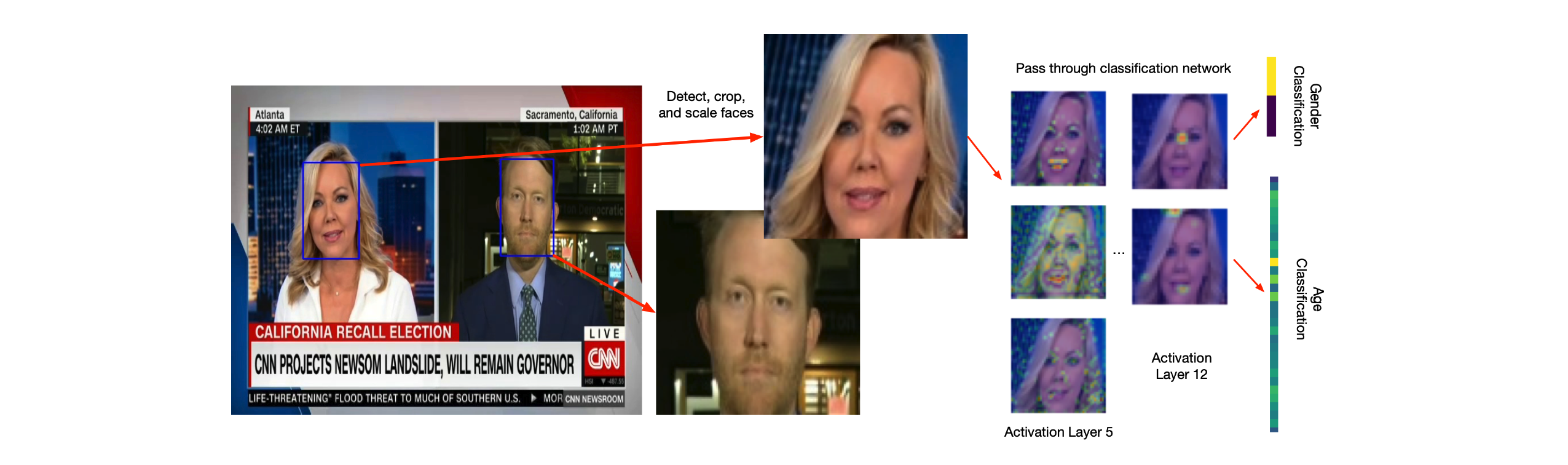

Deep learning is part of a broader family of machine learning methods based on artificial neural networks with representation learning

Learning can again be supervised, semi-supervised or unsupervised

Generally refers to large neural networks with many hidden layers

Originally developed to deal with image recognition, now also adapted for text analysis

Use the combination of words, bi-grams, word-embeddings, rather than feature frequencies

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

A machine learning technique for natural language processing, pre-training and developed by Google

A deep learning model in which every output element is connected to every input element, and the weightings between them are dynamically calculated based upon their connection

BERT is pre-trained on two different tasks: Masked Language Modeling and Next Sentence Prediction.

There is a new package (very recently released) that allows to use such pre-trained, large scale language models in R

If you are interested check the package “text”: https://r-text.org/

But: Be mindful! Running a BERT model can take a long time and might even require a more powerful computer than yours!

Is it okay to use a model we can’t possibly understand?

Machine learning in the social sciences generally used to solve an engineering problem

Output of Machine Learning is input for “actual” statistical model (e.g., we classify text, but run an analysis of variance with the output)

Machine learning is a useful tool for generalizing from sample

It is very useful to reduce the amount of manual coding needed

Many different models exist (each with many parameters/options)

We always need to validate model on unseen and representative test data!

van Atteveldt, W., van der Velden, M. A. C. G., & Boukes, M.. (2021). The Validity of Sentiment Analysis: Comparing Manual Annotation, Crowd-Coding, Dictionary Approaches, and Machine Learning Algorithms. Communication Methods and Measures, (15)2, 121-140, https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1869198

Su, L. Y.-F., Xenos, M. A., Rose, K. M., Wirz, C., Scheufele, D. A., & Brossard, D. (2018). Uncivil and personal? Comparing patterns of incivility in comments on the Facebook pages of news outlets. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3678–3699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818757205

(available on Canvas)

Boumans, J. W., & Trilling, D. (2016). Taking stock of the toolkit: An overview of relevant automated content analysis approaches and techniques for digital journalism scholars. Digital journalism, 4(1), 8-23.

Günther, E. , & Domahidi, E. (2017). What Communication Scholars Write About: An Analysis of 80 Years of Research in High-Impact Journals. International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 3051–3071

Hvitfeld, E. & Silge, J. (2021). Supervised Machine Learning for Text Analysis in R. CRC Press. https://smltar.com/

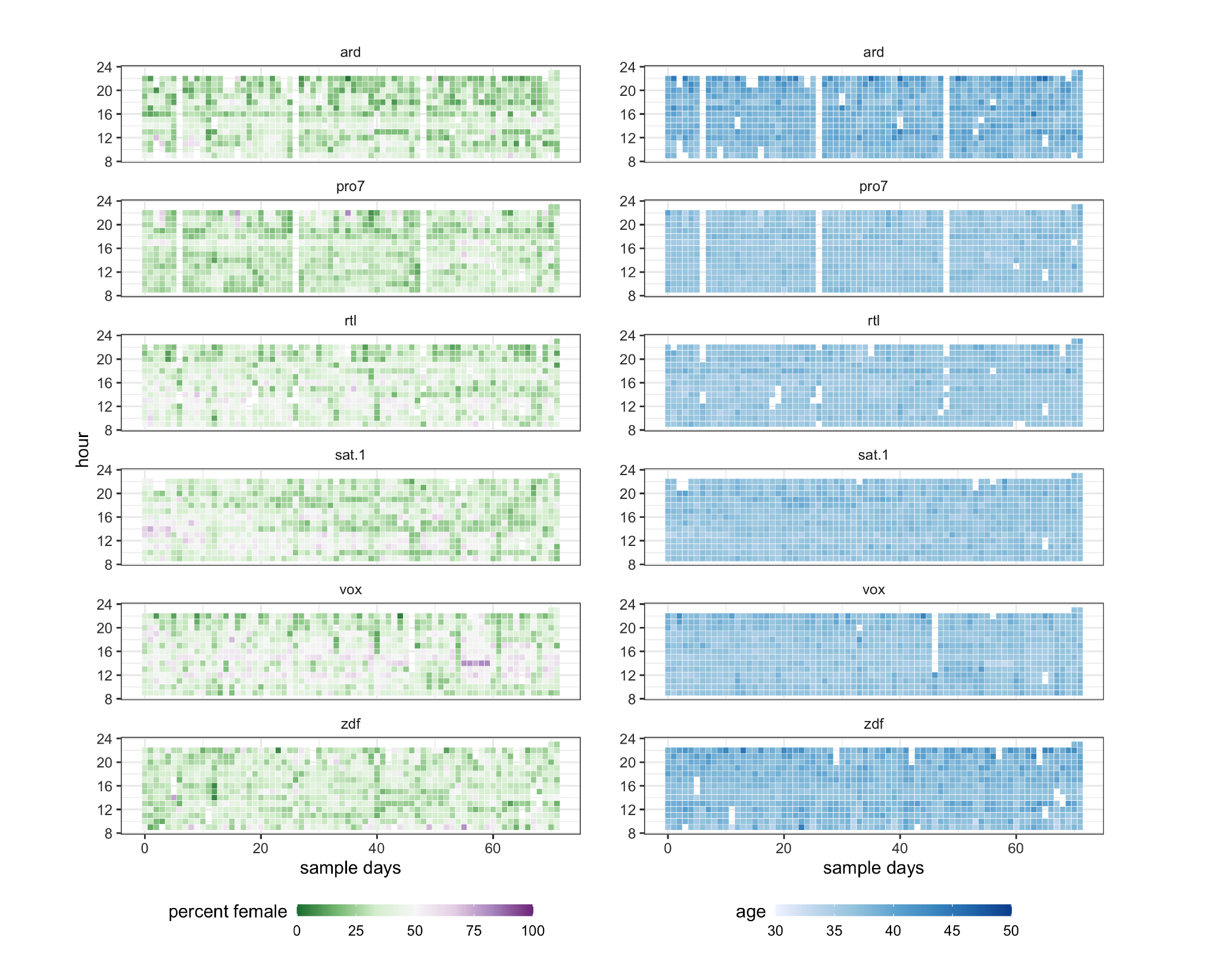

Jürgens, P., Meltzer, C., & Scharkow, M. (2021, in press). Age and Gender Representation on German TV: A Longitudinal Computational Analysis. Computational Communication Research.

Lantz, B. (2013). Machine learning in R. Packt Publishing Ltd.

Scharkow, M. (2013). Thematic content analysis using supervised machine learning: An empirical evaluation using german online news. Quality & Quantity, 47(2), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9545-7

Su, L. Y.-F., Xenos, M. A., Rose, K. M., Wirz, C., Scheufele, D. A., & Brossard, D. (2018). Uncivil and personal? Comparing patterns of incivility in comments on the Facebook pages of news outlets. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3678–3699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818757205

van Atteveldt, W., van der Velden, M. A. C. G., & Boukes, M.. (2021). The Validity of Sentiment Analysis: Comparing Manual Annotation, Crowd-Coding, Dictionary Approaches, and Machine Learning Algorithms. Communication Methods and Measures, (15)2, 121-140, https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1869198

Van Atteveldt and colleagues (2020) tested the validity of various automated text analysis approaches. What was their main result?

A. English dictionaries performed better than Dutch dictionaries in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

B. Dictionary approaches were as good as machine learning approaches in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

C. Of all automated approaches, supervised machine learning approaches performed the best in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

D. Manual coding and supervised machine learning approaches performed similarly well in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

Van Atteveldt and colleagues (2020) tested the validity of various automated text analysis approaches. What was their main result?

A. English dictionaries performed better than Dutch dictionaries in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

B. Dictionary approaches were as good as machine learning approaches in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

C. Of all automated approaches, supervised machine learning approaches performed the best in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

D. Manual coding and supervised machine learning approaches performed similarly well in classifying the sentiment of Dutch news paper headlines.

Describe the typical process used in supervised text classification.

Any supervised machine learning procedure to analyze text usually contains at least 4 steps:

One has to manually code a small set of documents for whatever variable(s) you care about (e.g., topics, sentiment, source,…).

One has to train a machine learning model on the hand-coded /gold-standard data, using the variable as the outcome of interest and the text features of the documents as the predictors.

One has to evaluate the effectiveness of the machine learning model via cross-validation. This means one has to test the model test on new (held-out) data.

Once one has trained a model with sufficient predictive accuracy, precision and recall, one can apply the model to more documents that have never been hand-coded or use it for the purpose it was designed for (e.g., a spam filter detection software)